The cardboard box labeled “CLOTHES” sat in the driveway next to a duffel bag that smelled a hint of mildew, like the basement. Summer heat radiated off the asphalt on the recently paved driveway. I was loading my mom’s 2007 Lincoln MKX, borrowing it, since my ‘90-something Cadillac Seville couldn’t be trusted to make it to New York.

Inside the boxes: sheets from home, a giant Franklin binder, well-worn wrestling gear, and the basic course catalog for Tompkins-Cortland Community College.

The dogs were barking and running through the side yard, perpetually torn up by my father’s tractor. I closed the trunk and stood there for a second. Then I got in the driver’s seat, adjusted the mirror, and backed out. 9:47 AM on a Tuesday. The Lincoln smelled like coffee and old leather.

Some gap years include working to pay for college or a year-long immersion in other countries; mine looked a bit different. I ended up signing up to join the regional training center and take classes at a local community college. This gap year experience would go on to be one of the most focused times of my life. There was still no purpose, but there was a goal: get into Cornell.

Note: this essay is a second part, if you are interested in reading part one, you can find that here.

My days were spent predominantly training technique, strength, conditioning, and mental fortitude. Coached by a man both incredibly grounded and clinically insane; my fellow class of gap year athletes and I casually held the push-up position for over an hour, hung by our fingertips from beams 15 feet off the ground, and ran the same impossible time, something like 32 seconds (after already running equally impossible 400 and 800 times) for a 200-meter dash1 between the hours of 4 PM and 9 PM all the while watching the Cornell football team start and complete practice while we continued to attempt to have everyone make the same time. No hamstrings, no lungs, no shins were spared.

Over the course of this year, I grew from 5’8, 125 pounds to 5’10, 150 pounds. I competed at 141 pounds at multiple open tournaments, almost exclusively going 0-2 barbeque2 while many of my teammates took home hardware. This sucked, and for the old me, this would have been devastating, but I had a different goal than many of my teammates—I was still working toward my acceptance to Cornell.

The Art of Refereeing

Wrestling, for all its ancient origins, gets thoroughly shafted by American culture. It exists in a state of neglect: underfunded, nearly invisible in broadcast media except for occasional Olympic coverage (where commentators inevitably butcher the basic rules), and competitions are compressed into pressure-cooker tournament formats that would be considered inhumane if imposed on athletes in more prestigious sports.

The irony is that wrestling’s most passionate supporters often become its harshest critics, transforming themselves into a jury system that scrutinizes every referee decision, coaching strategy, and administrative choice through spammed posts on Facebook and niche online forums.

Wrestling is drenched in judgment, the psychological environment as demanding as the physical one. Your average wrestler develops a hyperawareness of the referee’s positioning, who their opponent is, if they conducted their warm-up routine correctly, their coach’s anxiety level, their parents’ expectations visible in peripheral vision, and the countless distracting matches occurring on adjacent mats. Fight or flight at the sound of a whistle.

The wrestling referee’s decision-making process is remarkably impervious to both objectivity and consistency. What constitutes a pin at 10:00 a.m. in the championship bracket bears only a nominal resemblance to what constitutes a “pin” at 8:47 p.m. in consolations, when the maintenance staff is rolling up the unused mats and the director is watch-tapping a “hurry up” gesture. The most tentative calls become accompanied by the most emphatic gestures, as though the performance of authority might retroactively validate a ruling that was, in reality, based primarily on the referee’s desire to create narrative symmetry in a match that has gone on too long.

This peculiar theater of subjective authority became intimately familiar to me when I took up refereeing youth matches during high school—another odd job at an even lower pay scale than the $5.25 I earned at the movie theater. What I witnessed from inside the striped shirt complicated my cynicism about those inconsistent calls.

The refs who had done it long enough—the practice became an art of its own. These guys were legends. Every tenured youth coach knew them by name—Gary, Scott, Steve, Joe—always stated with a slight disdain, but also a strange amount of respect due to any bad calls that had favored them in the past.

What struck me most about these veteran refs was how they’d found purpose in this thankless role—a purpose that existed entirely outside conventional notions of career advancement or social prestige. They’d mastered the art of imposing order on chaos, of applying subjective judgment to supposedly objective rules, all while being perpetually second-guessed by parents who’d never opened a rulebook. Their commitment seemed to exist in direct opposition to the purpose-as-economic-advancement narrative I’d been fed.

In their devotion to youth wrestling, I glimpsed an alternative relationship to purpose: not as a path to upward mobility, but as a way of carving out meaning in a specifically chosen corner of human experience, however obscure or undervalued. They had found their particular chaos and chosen to inhabit it fully.

The Obsession

After a year of coursework and training I applied to Cornell in the spring. I was denied and became angry, frustrated, and even more hell-bent on getting in. After a brief existential inquiry and crash out, I spent the next year taking as many credits as possible (8 in the summer and 17 in the fall), attending open office hours of Cornell professors with questions on their research, networking with as many people in the admissions office, dean’s office, and advisory board as I could.

This is what I credit to getting accepted into Cornell.

Wrestling, yes, got my foot in the door more than any other type of experience would have, but I was not nearly talented enough and the school is not athletic-focused enough for my wrestling to have done very much in leading me to actually get accepted. Something that gave me imposter syndrome for my entire tenure, thereafter, and still, at times, today.

My acceptance arrived via a phone call from the director of admissions himself—a man whose voice I recognized from the dozen or so times I’d called his direct line (which I’d memorized) after emailing with excessive frequency—a communication that, I will admittedly say, was not in the slightest authentic, but rather the culmination of what was essentially a carefully orchestrated operation disguised as what college counselors euphemistically call “demonstrated interest,” my more self-aware present-self recognizes as “recognition through repetition” which happened to pay off.

The timing of this acceptance was deep into “waitlist season,” and arrived less than 18 hours after my twentieth follow-up email, this time inviting him to come watch the competition taking place mere meters away from his office situated on the other side of the courtyard shared with Barton Hall, a gymnasium converted from an airplane hanger, where I was competing that Sunday. It seems clear in retrospect that my application existed in a state of indeterminacy, neither accepted nor rejected but suspended in an administrative netherworld until my invitation email functioned as a sort of catalyst of realization.

This is the unacknowledged truth about elite college admissions: that beneath the veneer of standardized metrics and carefully constructed rubrics lies a system so capricious that it borders on mystical, where acceptance often hinges not on the rational evaluation of achievement but on the synchronicity of your email arriving precisely when the director of admissions was wondering, “why does that name sound so familiar?”

The Call

I received the call while at the very competition mentioned in my email—so narratively convenient that it still feels staged, like a climactic scene of a particularly heavy-handed indie film about class mobility. The number appeared as “Restricted3” and I nearly ignored it, being that I was actively preparing to compete, but I had a strange feeling. When I answered, the voice identified itself as “Ian Schachner,” the ILR school’s director of admissions, and I experienced a brief suspension of cognitive function followed by an intense flood of stress hormones that made me feel as if I was watching myself from a bird’s eye view.

The conversation exists in my memory as disjointed fragments: his congratulations, my stammered thank you, his enthusiasm for me joining the school and encouragement for the rest of the competition, my promise to “make Cornell proud” (a pledge that conveniently overlooked the question of whether I should also make myself proud).

What I remember with perfect clarity is the blend of emotions that followed: relief so profound it bordered on religious experience, pride so intense it verged on narcissism, and—most predominantly—an immediate onset of textbook impostor syndrome, the psychological conviction that my acceptance represented not achievement but clerical error.

The circumstances were too strange, the timing too convenient, that it felt less like earning a spot and more like winning an obscure lottery with rules that had never been fully explained to the participants. Was I a statistical anomaly they needed to round out their demographic spreadsheet? Was my wrestling background—a sport whose Ivy League presence is perpetually overshadowed by rowing and lacrosse—exotic enough to warrant a second look but familiar enough not to frighten the development office? Was there some negligible box-checking practice or even possibly only accepted because another transfer declined their acceptance to the program?

The Price of Getting What You Wanted

The acceptance triggered anxiety so strong I began having full shaking panic attacks, insomnia, and within 78 days started taking full doses of Zoloft for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. The reason I began the Zoloft was actually to lessen the physical symptoms of anxiety, primarily the manifestation of Acid Reflux (unresolved by OTC Prilosec) that lead to 5 consecutive dental visits resulting in cavity fillings due to the acid dissolving the enamel of my molars.

This physical manifestation of anxiety also led to Bruxism and TMJ, my jaw grinding itself back and forth unconsciously to the point where I had grinded through a mouthpiece in my sleep. I was so goddamn sure that I had some sort of mouth, jaw, or throat cancer that I began writing pitiful end-of-life poetry in texts I would send to myself in case I were to suddenly pass away and people were to look through my phone to remember things about me.

Was it worth it?

Ultimately I’ve learned that this question is a trap and inherently the answer must always be yes, unless you crave internal chaos. Yes, I would say it is worth it and here is why: I am writing an essay half a decade after graduating, having worked in roles I didn’t even know existed, roles which were initially thrilling and exciting and then eventually miserable, trying to validate to myself that everything I have put into this series of events has been all done with a purpose for a purpose and that means it is worthy of praise and self-love.

But deep down that purpose has muddied my mind and driven me to do things that my inner child couldn’t have done, but more importantly wouldn’t have done. This jarring disconnect, this feeling of being fundamentally altered and stressed to the breaking point, wasn’t what Cornell advertised, but it formed the real curriculum.

What I Actually Learned

By the time I graduated, the knowledge I’d truly accumulated wasn’t found in course catalogs but forged in that internal conflict. It fell into several distinct categories entirely different from the marketing materials’ promises:

Self-Knowledge (Uncomfortable): I learned that I possessed a social adaptability that is simultaneously a survival skill, people-pleasing, and a form of self-betrayal. The ability to code-switch between the linguistic patterns of my rural Michigan upbringing and the carefully modulated speech of the Eastern Seaboard elite. It works until it doesn’t. After approximately 168 hours of performing “Upper-Middle-Class Educated Person,” the identity vertigo hits and I find myself in bathroom stalls of academic halls, silently dealing Euchre hands behind my eyelids and craving the fall from a tall bridge into water.

Realization (years later), this imposter syndrome wasn’t a syndrome; it was an accurate barometer inside an institution that reproduces class while claiming to transcend it.

Chaos Theory (Applied to Human Systems): I learned that chaos—the thing I’d been told education would help me escape—was actually the governing principle of every supposedly meritocratic institution. Academic achievement operated less like a linear progression and more like birdshot, influenced by factors ranging from which TA graded your midterm to whether your language skills could convey the difference between “earned” or “deserved” to a stubborn professor whose academic rival had recently published in a more prestigious journal.

The university’s choice to print median grade on transcripts—sold as “fairness”—was damaging in nearly every case. That uncommon transparency quantified each student against peers that no employer or grad program had requested, functioning less as honesty than ritualized penalty.

Most telling: the people least rattled by all this chaos were those most insulated by family wealth. Their serene navigation read not as superior competence but as the calm of someone for whom failure has never carried real risk.

The Precise Topography of Weakness (Personal and Institutional): I mapped my soft spots: the way I shrank in seminars where classmates casually cited theorists I hadn’t read; my reflex to defer to authority even when I could hear the hollowness of the pronouncements; and my knack for catastrophic thought spirals triggered by the most innocuous stimuli—a slight uptick in heart rate during class discussion that I would interpret as the onset of a cardiac event; a past Tinder match appearing in lecture that would send my mind scripting the gossip network that must surely be forming about my dating history.

More valuably, I trained an eye for institutional weakness: fractures in the meritocratic façade, the performative nature of its diversity initiatives, the way its administrative responses to suffering often resembled PR damage control more than actual care. Large institutions are essentially contradiction-management machines, perpetually reconciling their stated values with their operational requirements through increasingly complex and convoluted rhetorical contortions.

The most grounded I felt while at Cornell was in two places: the Friedman Wrestling Center, and 2nd Dam, a dammed-up reservoir along 6 Mile Creek, where locals gorge jumped at heights of 20, 40, and 60 feet. Somehow, no matter where I am, I instinctively find these sacred locations, where going airborne before landing in icy water can make any pain endured prior, during, or for several hours after, worth it.

The Liberal Arts Education (As Actually Experienced vs. As Marketed): What was marketed: “A transformative intellectual journey across disciplines, where students engage with diverse perspectives and develop critical thinking skills through dialogue with world-class faculty dedicated to undergraduate mentorship.”

What was delivered: adjunct-taught survey courses that use quizzes as attendance in echoing lecture halls; office hours perpetually scheduled during your other classes; TAs cramming material three days before they’re meant to teach it; and, every so often, a lightning-strike of real learning—almost by accident—in the margins: a hallway conversation after class, a throwaway line in feedback, a visiting speaker you attended for extra credit whose ideas quietly rewired your brain.

I did absorb some specific knowledge about industrial and labor relations—enough to recognize that many labor regulations are essentially gentlemen’s agreements with minimal enforcement mechanisms; that HR departments function primarily as corporate immune systems designed to neutralize threats to the organization rather than advocate for workers; that the history of American labor is a blood-soaked saga systematically sanitized in mainstream education.

But this factual knowledge occupies a smaller cognitive footprint than the meta-knowledge about knowledge itself: how it’s produced, validated, marketed, and distributed through institutions that simultaneously democratize and gatekeep it.

Purpose was supposed to clarify. Instead, it complicated everything. What I learned was simpler: want something, name the cost, and decide if you’ll pay it. I still test that math the same way I did at 2nd Dam—go airborne, hit cold water, see what still feels worth it. The most difficult realization to manifest was recognizing that the options: Purpose, Perfection, and Practice exist in every choice we make, and when you choose one, you reject the others.

In seeking purpose, I followed the path that made sense: good college, good job, good money, good life.

In holding myself to perfection, I turned failure into catastrophe rather than opportunity, boxing myself into one definition of success—and earning a decade’s worth of anxiety in the process.

In time, through reflection, I discovered a third option I’d once known instinctively: that I was most at peace, most comfortable, most successful when I simply practiced, tested things out, checked the water’s temperature by jumping feet first from 50ft up.

Below you can find some artifacts from that time period:

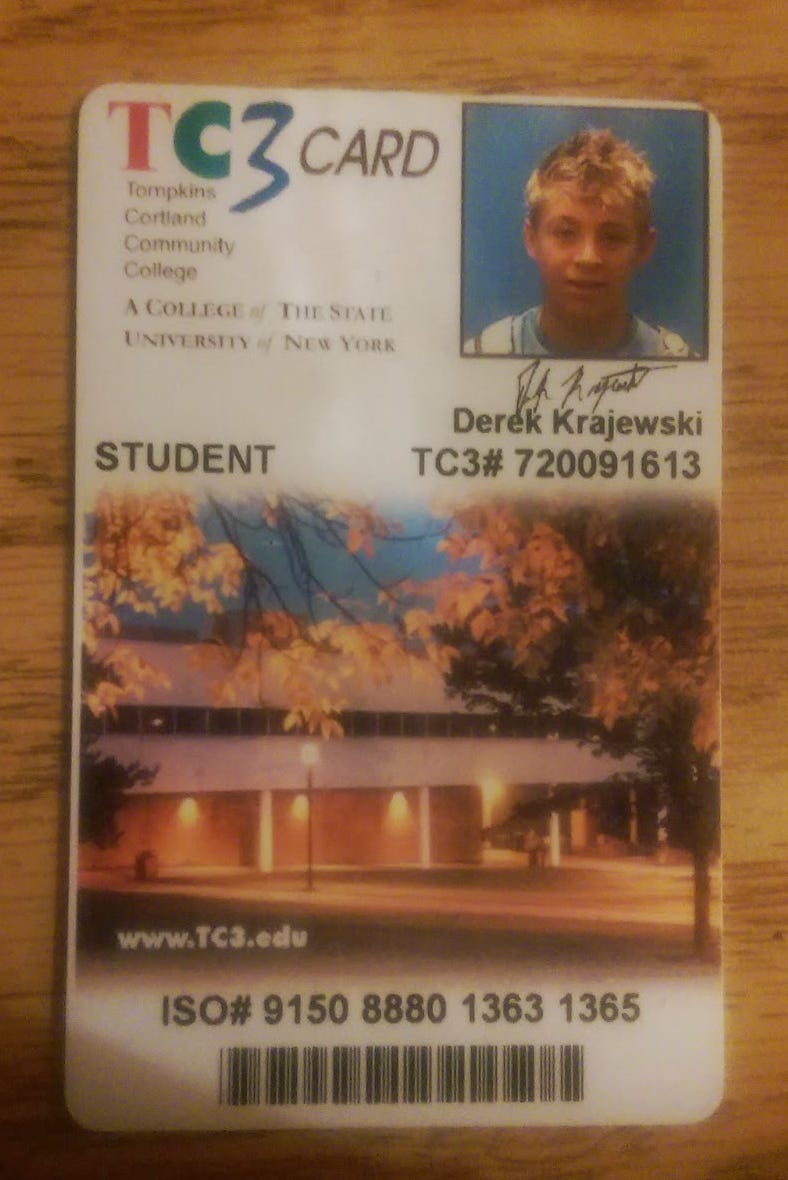

My TC3 Card—crazy how young I look—even in 2015, I don’t think that is what the average Freshman in college looked like.

Ithaca Falls; back before they gated the entrance.

A card from all of my teammates after I got accepted—after the tournament I took some time and cried into the card in my room. I still have this card today.

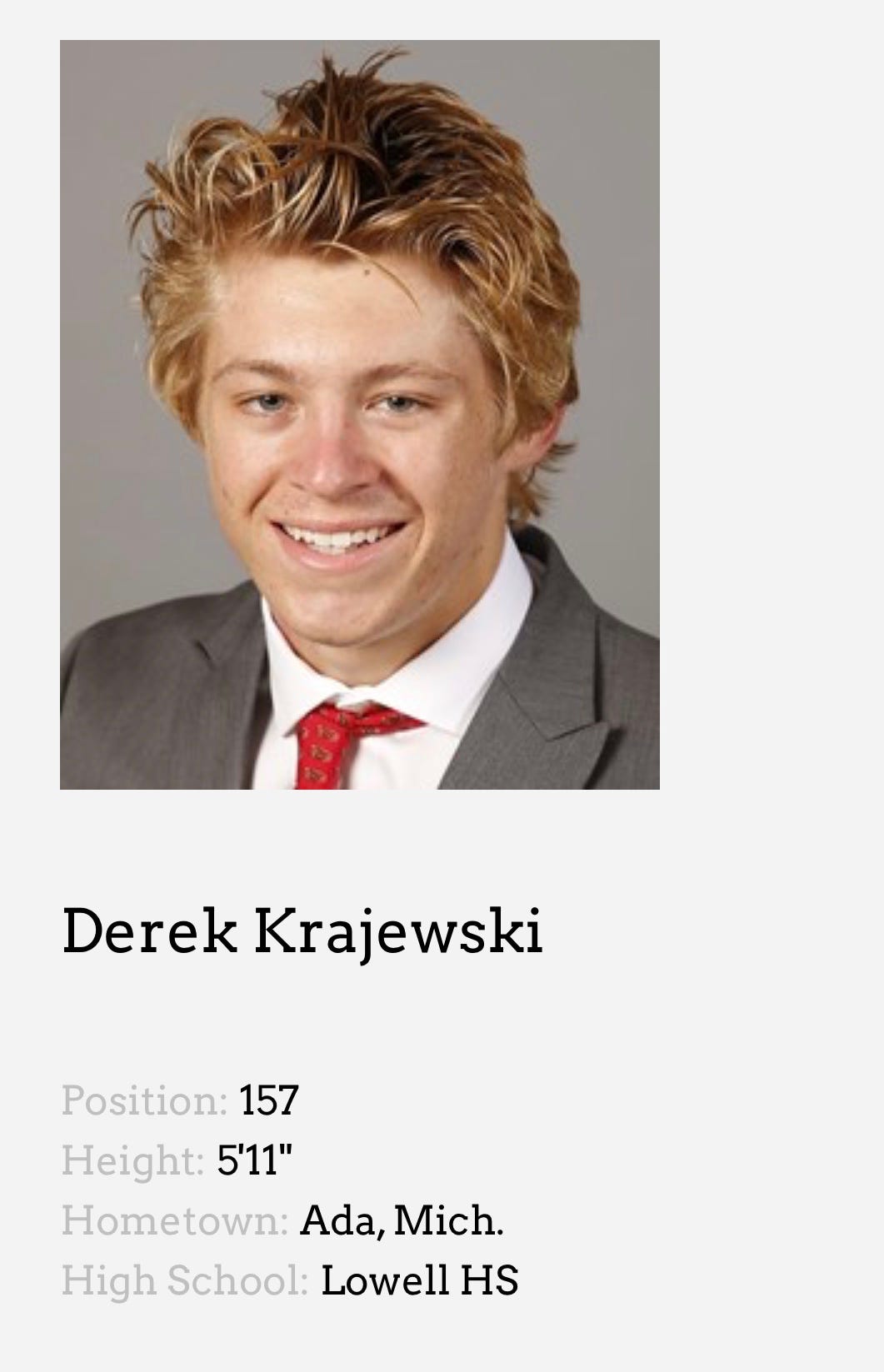

My Cornell Athletics photo, not my best work.

Bringing friends from Michigan to Second Dam and jumping from increasingly high spots was my safe space.

Despite the tone, this essay is NOT anti-higher-education or anything of that nature. I had an incredible college experience, made some of the best friends, and experienced MANY things I never could have fathomed, graduating from Cornell is one of my proudest accomplishments—right up there with getting accepted. (more on this in another essay)

The funny thing was, as he began to recognize we would never all make the time began to hint at and encourage us to cheat, in order to make it or “win” by any means necessary.

“Oh-and-two, barbecue”: two straight losses and you’re out—time to pack your headgear while everyone else keeps wrestling.

Which, at that point in time in my life, was typically either a friend prank calling me or a faux debt collector looking to get my social security number; this time, it was neither.